The Report

2.4 Type of program

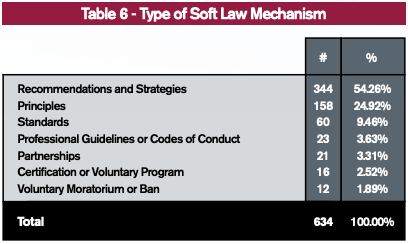

The taxonomy of soft law programs was inspired by scholarship that examined its diversity [6]–[8]. Not all programs are created equally and, in this project, they were divided into seven categories (see Table 6). We find that the vast majority (~79%) are either principles or recommendations and strategies. In addition, we compiled one of the largest lists of principles related to the governance of AI applications and methods available in the contemporary literature.

2.4.1 Recommendations and strategies

This category contains two types of programs that comprise over half of the database (344 programs representing 54% of the sample). Strategies are roadmaps that highlight the direction an entity wishes to or should pursue. Meanwhile, recommendations were found in the form of suggestions, proposals, or evidence-based actions meant to improve an organization’s status quo. Our team combined these programs because they tended to overlap.

The vast majority of recommendations and strategies are developed in-house by the entities that intend to adhere to them. However, the database incorporated a limited number of recommendations created by third-parties. To qualify, a substantive expectation of compliance needed to exist between organizations. For example, governments published AI specific strategies detailing plans to improve a country’s AI competitiveness in research and development, transportation technologies, education, ethics, and other issue [34]–[36]. Many did so by forming multi-stakeholder alliances with non-profit institutions and/or the private sector (Gov-Np and Gov-Ps) [30], [37], [38]. Excluded from this category were programs generated by non-profits or private sector entities directed at institutions with whom they had no links to (pecuniary or non-pecuniary).

2.4.2 Principles

As broad statements that serve as high-level norms, principles have been the focus of important efforts aimed at implementing the soft law governance of AI [1], [2]. This database offers one of the largest known compilations of these programs containing 158 examples [39]–[41]. In contrast to the overall trend seen in Figure 1 (see section 2.5), most of the entities responsible for developing principles are in the private sector, followed by government with ~31% and ~28%, respectively. Interestingly, this research effort uncovered that, despite their high-level nature, a quarter of principles (38) incorporate or mention enforcement mechanisms (see section 2.6).

2.4.3 Standards

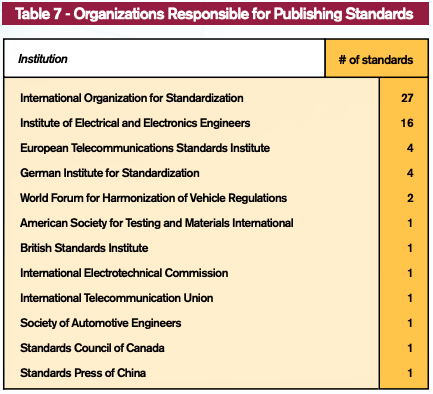

Any program developed by a standard-setting organization (SSOs) that addresses the technical needs of a field is within the scope of this category. As seen in Table 7, 12 organizations were responsible for the 60 standards in the database. As is customary with SSO’s, virtually all programs are influenced by the multi-stakeholder input of governments, non-profits, and the private sector. In addition, their enforcement relies on employing an external entity whose job it is to verify compliance with the terms of a standard.

2.4.4 Professional guidelines or codes of conduct

These programs describe behavior expectations applicable to individuals that work with AI applications or methods. They represent less than ~4% of the instruments in the database and are developed by a range of organizations including: professional associations who define the base level behavior expected from their members [42]–[44], industry associations who agglomerate private sector firms [45], and individual firms [46], [47]

2.4.5 Partnerships

A partnership is an initiative in which two or more entities collaborate to advance an agenda. Corresponding to ~3% of the database, these alliances are opportunities to advocate for an issue or generate synergies between stakeholders. The database bears witness to various flavors of these programs. Governments and the private sector may join to tackle a framework for responsible AI [48], governments cooperate to study alternatives for the technology’s governance [49], and the private sector can work with a non-profit to advocate for ethical data governance [50].

2.4.6 Certification or voluntary programs

This soft law category includes two types of programs that represent ~2.5% of the sample. A certification is akin to a market signal, in the form of a “seal of approval” or statement, that indicates compliance to a set of pre-defined characteristics. Certifications exist for a number of issues including a commitment to minimizing the “abuse of facial analysis technology” [51] and the accountability of robotic products [52]. Excluded from this category are any programs related to educational certifications.

A voluntary program is a government initiative that invites non-government entities (private sector and non-profits) to comply with a non-binding set of actions or guidelines. Few of these where identified in this research effort. Among them, the government of Finland developed a program challenging local businesses to consider the ethical ramifications of their AI-based products [53].

2.4.7 Voluntary moratorium or ban

Moratoriums and bans are characterized by a call of action to avoid or cease the usage of an AI application or method. Generally, they target technologies that cause harm or negatively affect individuals. Only 12 of these programs were found in the sample. Ten focus on autonomous weapon systems [54]–[56] and the other two target AI-powered toys [57] and deepfake images [58].