The Report

2.6 Enforcement

In the pursuit of managing the consequences of AI, institutions throughout the world have created a range of soft law programs (e.g. principles, guidelines, strategies), many of which lack enforcement or implementation mechanisms. In fact, oft cited in discussions of soft law is its main weakness, its voluntary nature. In other words, all soft law programs rely on the alignment of incentives for implementation to take place, rather than the threat of direct enforcement. The literature on the subject offers insights into the menu of options available to facilitate this alignment [7], [77]. However, scant attention has been dedicated to documenting the trends in their overall existence or use in existing AI soft law programs.

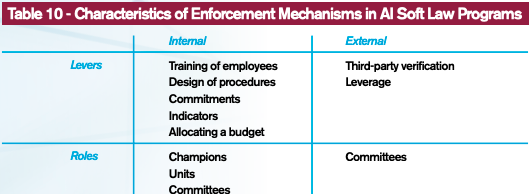

This section addresses this research gap by identifying the organizational mechanisms, if present in a given soft law measure, that catalyze compliance, improve enforcement, or are used to plan for the implementation of soft law programs directed at AI. Further, it examines their characteristics and proposes a classification consisting of four categories: internal vs. external and levers vs. roles (see Table 10).

Internal mechanisms are those whose operation depend on resources available within an organization. Naturally, external mechanisms are the opposite. They invite the participation of independent third parties to play a role in overseeing the implementation of a program. Within external and internal mechanisms, we identified levers. Levers represent the toolkit of actions or mechanisms that an organization can employ to implement or enforce a program. Its counterpart is characterized as roles. It describes how individuals, the most important resource of any organization, are arranged to execute the toolkit of levers.

This section is divided into four parts that analyze the mechanisms within the quadrants of Table 10. Readers will find that the voluntary nature of soft law need not, and often does not, represent an obstacle for a program’s enforcement. Stakeholders within the database harness the diverse menu of levers and roles to transition their soft law program from an idea to actionable AI governance.

2.6.1 Internal levers

The organizational toolkit available to implement or enforce soft law programs are denominated levers. One way to distinguish the five mechanisms listed in this quadrant is by their objective. The first three are designed to improve or guarantee the operation of a program through educational initiatives that inform or train employees, generate procedures to guide their actions, or allocate a budget to make a program’s operation possible. The latter two are centered on goal-setting activities that motivate action such as making public commitments or creating indicators to measure the success of activities.

2.6.1.1 Educating the workforce

Educational programs are a means to instill new norms or ideas to an organization’s workforce. In the database, we found that these mechanisms were an opportunity to shape how employees interacted with a soft law program.

Specifically, some training initiatives were designed to introduce staff to an employer’s approach for responsibly dealing with AI (explaining its principles or guidelines) [33], [78]. Others were directed at assisting employees in recognizing the intersection of AI and ethics, explain how to ethically develop products and applications using this technology, or build an understanding of the professional ethics expected in the field [33], [39], [78]–[80]. Mechanisms were also tailored to explain the negative effects of AI and instruct individuals on, for example, the actions they could take to “address potential human rights risks associated” with this technology [67].

Although most education-focused levers were generically described as trainings or workshops, one organization complemented these efforts by testing the creation of an “internal ethics certification” [81]. Its role within the firm was to generate an internal compliance tool that verified if staff with responsibilities directly associated to AI understood a firm’s AI ethics guidelines.

2.6.1.2 Creation of procedures

Once a soft law program is created, organizations may seek to enforce it by altering how their employees or representatives perform their duties through the creation and implementation of internal procedures. A wide scope of these type of levers was found in the database. For instance, firms created guidelines that allow employees to subjectively assess issues related to AI. This was the case in a firm who directed managers to evaluate the design of their AI products with an online questionnaire geared towards uncovering “potential human rights risks associated with the use of [AI]” [67].

Organizations also integrated soft law by developing procedures that employees are required to enforce (e.g. guidelines, review processes, daily meetings, testing procedures, among others) [39], [80], [82]. In one company, guidelines “must be followed by all officers and employees […] when utilizing AI and/or conducting AI-related R&D” [66]. In another, employees involved with the development and testing of AI applications were instructed to implement a review process, given the power to flag concerns and, if these were escalated, could ultimately halt the firm’s work in testing an AI-based technology that was determined to be problematic [82].

2.6.1.3 Allocating a budget

Assigning resources to a soft law program is one of the strongest commitments an entity can make to guarantee its enforcement. The availability of a budget increases the likelihood that a set of tasks or actions will be implemented because the organization’s management has deemed it enough of a priority to devote resources to it.

We found that such resources were allocated to two types of initiatives. First, governments assigned budgets for the implementation of their AI strategies. For one European government, this meant setting aside €20 million to “create a good basis for the development of automated driving” [83]. A North American counterpart bequeathed a fund of CA$125 million to a research institution to “develop and lead” its AI strategy [84].

Secondly, we observed that resources were assigned to fund research initiatives and partnerships. These investments were made as one-off’s, such as the apportionment for a multi-government research alliance [85], or on an annual basis, as was the case for the €2 million pledged by the Indian and French government for “basic and applied research projects, scholarships for training and research, exchange of experts and research projects, and awareness-raising measures” [86].

In terms of partnership, we uncovered programs that involve a variety of stakeholders contributing funding. For instance, the state of Karnataka in India partnered with a trade association to fund a Centre of Excellence for data science and AI, two German research institutes joined forces to create an AI center with the support of several levels of government, and Bank of America associated itself with Harvard University to support AI research [87]–[89].

2.6.1.4 Commitments

Publicly committing to a course of action is a signal to society that generates expectations about an organization’s future actions. This section found a limited number of entities that make such promises to stakeholders. Although these commitments do not necessarily provide explicit detail on their enforcement, they can publicly bind the organization to act. In this regard, one firm asserted that their AI principles would “actively govern our research and product development and will impact our business decisions” [68]. Another stated that “all products and services are implemented and utilized by […] employees, customers and partners” to “prevent and address human rights issues arising from AI utilization” [90].

General Electric signaled stakeholders about a variety of commitments related to their AI efforts [91]. The first commitment was to strive for diversity in their data science teams and to procure databases that reflected the population under analysis. The second commitment targeted the transparency of how their systems use data in their decision-making process. Finally, the last commitment is to work with stakeholders to ensure that the firm does “AI right – practically, methodically and for the benefit, safety and privacy of the patient” [91].

Signaling is not restricted to the private sector, as governments and multilateral organizations alike employ it. In one government strategy, we found that the agency implementing a soft law program committed to self-assess their goals based on advances in AI’s state of the art [92]. Lastly, officials representing national governments in a multilateral pact agreed to annually review the “appropriate measures in order to adequately react to the emerging evolution of Al” [93].

2.6.1.5 Indicators

Indicators are akin to goal posts. Setting them allows an organization to evaluate its progress in achieving objectives and evaluate if taking further action is merited. Few examples of indicators as forcing mechanisms were found in the database. When identified, they were located within government strategies.

One government’s AI strategy committed to create indicators in the near future, but in the meantime promised to track how stakeholders reacted to its strategy’s activities [94]. A different government included AI as one of the technologies to be used in updating the administration of government. For this purpose, it developed indicators specific to the technology including: percentage of ministry families that use AI for service delivery or policy making with the goal of “all ministry families to have at least one AI project” [95]. Another government, whose strategy was completely devoted to AI, assigned performance indicators to each of its objectives [92]. It incentivized staff to achieve them by making their results a factor in determining future budget allocations [92].

2.6.2 Internal roles

The previously described levers were executed by individuals, groups of employees, or units within an organization. These individuals were assigned responsibilities with the purpose of steering, advising, or implementing soft law programs. It is self-evident that people are the most important institutional resource for the enforcement of soft law. Any program for that matter, including those directed at AI, will not function appropriately unless they are coordinated, championed, and pushed forward by individuals. This section examines the role of human resources in the execution of AI soft law programs. The analysis encountered three types of internal human resource roles: individual positions (e.g. champions), organizing groups of people through units, and the development of employee-led committees.

2.6.2.1 Champions

A champion is an individual who is bestowed the power within an organization to promote, educate, or assess issues related to an AI program. As expected, the power and responsibilities given to people in this role are wide-ranging. One government proposed the creation of an ombudsman to monitor the ethical practices of entities handling biometric technologies and how their associated data are utilized [96]. Another government created organizational archetypes (i.e. Chief Digital Strategy Officers and Chief Information Officers) to complement each other with the implementation of AI initiatives throughout the public sector [95].

In the private sector, AI champions have been assigned to assess how engineers understand ethics and transparency or identify if an AI-based product could produce a negative effect on the firm or society [67], [81]. Champions have also been given compliance responsibilities. One organization assigned two high level officers to evaluate high-risk products and determine if they satisfied an entity’s AI privacy and decision-making standards [97].

2.6.2.2 Units

The creation of a unit within an organization represents a concerted effort to formalize the attainment of an objective through a permanent internal structure. We found one example of an organization with a unit dedicated to the enforcement of AI-related programs. Specifically, Microsoft’s “Office of Responsible AI” is tasked with “setting the company-wide rules for enacting responsible AI,” “defining roles and responsibilities for teams involved in this effort,” and engaging with external efforts to shape soft law approaches to AI [40].

2.6.2.3 Committees

Internal committees or taskforces are entities whose composition includes representatives from within an organization (e.g. employees from executive management, engineering, human resources, legal, and product departments) [40], [98]–[100]. The role they perform varies by entity. In most cases, internal committees actively address the relationship between an organization’s AI methods and applications with its consequences. This can be in the form of overseeing AI-related processes, convening working groups, confirming that a firm’s outcomes comply with AI commitments and soft law programs, or updating these programs when necessary [40], [78], [99], [101], [102]. In other models, committees are given a mandate to engage with relevant stakeholders from within and without the firm to generate and maintain appropriate feedback on the company’s AI performance [100].

2.6.2.4 Interaction between governance levels

Few organizations publicly describe the relationship between different levels of their AI governance structure in detail. The ones that do, provide insights into the checks and balances in their implementation of soft law programs. In this database, the only organizations that provided this level of detail were Microsoft and Telefonica.

Microsoft built a structure in which its AI unit (Office of Responsible AI) and its internally-led committee (Aether) complement each other’s role [40]. In their own words, these bodies “work closely with our responsible AI advocates and teams to uphold Microsoft responsible AI principles in their day-to-day work” [40].

Telefonica developed a multi-tiered model. In it, a product manager can signal that a method or application of AI may have a negative impact on the company to an AI champion [67]. These champions are tasked to solve the problem with a manager. If that is not possible, or if it represents a reputational risk for the company, “the matter is elevated to the Responsible Business Office which brings together all relevant department directors at [the] global level” [67].

2.6.3 External levers

Within the organizational toolkits devoted to the enforcement of soft law, we found two levers that invited the participation of external entities: third-party verification and the use of leverage to compel the compliance of a target population.

2.6.3.1 Third-party verification

This mechanism entails the participation of an external entity in verifying the compliance to a set of guidelines. Standards, labels, and certifications are variations of programs that utilize third-party verification. In these cases, an independent entity is sought to reassure stakeholders on an entity’s compliance with desirable guidelines. On the other hand, professional organizations depend on their members, individuals affiliated with them, but employed by other entities, to enforce their codes of conduct.

2.6.3.1.1 Standards

The purpose of standard setting organizations is to generate technical norms directed at the needs of the field’s stakeholders. Entities interested in subjecting themselves to any of these standards have two choices on their level of commitment. In the first level, they can purchase the requirements of a standard and implement it by themselves. In choosing to do so, they are solely responsible for adhering to its rules. Which means that external parties have no means of verifying if the standard is adequately implemented.

Alternatively, entities can opt to hire a qualified third party to certify that the organization conforms to a standard’s requirements. Doing so, represents a forcing mechanism that incentivizes the alignment to a soft law program. Successfully following a standard, grants an entity with an endorsement that can be communicated to stakeholders. This project found 60 standards related to AI that were in development or currently available. Examples of standards titles include: Guide for Verification of Autonomous Systems, Algorithmic Bias Considerations, and the Ethical Design and Use of Automated Decision Systems.

2.6.3.1.2 Labels or certifications

Similar to standards, labels or certifications are a signal to the market. However, these mechanisms validate a product or process according to a set of parameters developed by an institution with a distinct point of view. Organizations voluntarily chose to subject themselves to these soft law programs to communicate the benefits of their products or services. The expectation is that this signal will generate a surplus of confidence in a target population (e.g. consumers, suppliers, government, among others). Many of these labels or certifications rely on third parties to verify an applicant’s compliance to the requirements of a program. Successful applicants gain the ability to communicate that an independent entity has verified their claims, giving consumers more reasons to trust them.

The labels or certifications in our database are managed by non-profits, professional associations, and governments. In addition, they can be divided into two categories. The first category includes labels applicable to a wide scope of products and services. In one case, a foundation created a quality mark meant to implement the transparency and trust principles it believes should be present in all robots [52]. The organization relies on independent auditors to confirm that an applicant has adhered to its precepts on a yearly basis. Another is a test program by a professional association that offers a series of marks to certify all types of AI-based “products, systems, and services” [103]. Finally, a partnership between a non-profit and a government is creating a certification program meant to verify that AI products are “technically reliable and ethically acceptable” [104]. This instrument is an ambitious overarching tool that attempts to examine a product’s “fairness, transparency, autonomy, control, data protection, safety, security and reliability” [104].

The second type of label or certification is specifically targeted at a particular application of AI. An example is the Safe Face Pledge mark meant for facial recognition technology. It requires participants to modify all internal procedures to comply with the values promoted by the creator of the label [51]. A different case is a collaboration between government, firms, and non-profits who are in the process of developing a certification for driving algorithms in Germany. This project aims to have firms upload their intellectual property into the system so it may analyze and “ensure their decisions are always favourable to the safety of the traffic around them” [105]. Lastly, a non-profit has created a seal tailored for the toy industry. It is designed to protect the rights of under-age individuals whose data and development is at risk from AI-enabled toys that could be used to exploit these vulnerable members of society [106]. The main target of this mark are parents who want their children to be safe from firms that could use the information they obtain from minors in a predatory manner.

2.6.3.1.3 Professional associations

Professional associations agglomerate individuals from throughout the world to share experiences, debate major issues in their field, and set standards of conduct. In our search for soft law programs, individuals that form part of major global and regional associations related to AI require that their members report ethics code violations [107]–[109]. In some cases, not doing so constitutes itself a violation. In this sense, compliance to this particular brand of soft law depends on third-party cooperation for its success.

2.6.3.2 Leverage

There are organizations who utilize their economic influence on others as leverage to compel adherence to soft law programs. In this analysis, we observed that two stakeholder groups were targeted: customers and suppliers.

One organization, a telecommunications firm, requested the compliance to its soft law program. Despite no mention of a binding mechanism, its documentation states that their AI ethical principles “must be observed by…business partners and suppliers” [110]. In contrast, firms can guarantee that their influence will affect the behavior of a target organization via written agreements. We found an organization that requires all of its customers and partners to adhere to its AI-related code of conduct [111]. In fact, if evidence of non-compliance is found, the firm reserves the right to terminate its business relationship. A similar commitment is required by a technology company with over 5,000 suppliers [97]. Each of them must agree to apply the firm’s standards on cyber security and data processing.

2.6.4 External roles

The main conduit for inviting external human resources to participate in the enforcement of mechanisms is committees or taskforces. They represent an opportunity to include individuals who differ from their internal counterparts because they imbue a distinct perspective to the operation of an organization.

2.6.4.1 Committees

Organizations value the input of outsiders because they provide a viewpoint that is informed by different ideas and environments. Inviting these individuals to a board, committee, or taskforce offers a platform to contribute their knowledge and perspective. This section identifies how four types of organizations (private sector, government, nonprofits, and professional associations) chose to harness these contributions to improve the implementation or enforcement of their AI-related soft law programs.

2.6.4.1.1 Private sector

Boards or committees (whether they are legally constituted or act in a consultative manner) act in the interests of a public firm’s shareholders by supervising the decision-making of its management. These bodies are composed of external members and are created specifically to deal with the risks and issues stemming from the integration or commercialization of AI.

They also differentiate themselves by their degrees of power. One firm’s board has a role limited to counseling it on specific areas of concern such as “diversity and inclusion, algorithmic bias and data security and privacy” [112]. Another was motivated to assemble a body to “help guide and advise the company on ethical issues relating to its development and deployment” of AI-based products [113]. A significant difference between these two examples is that the latter was given the power to veto a firm’s products and services. In fact, this board publicly declined to endorse the use of AI in a product, thus preventing its commercialization [114].

2.6.4.1.2 Government

Similar to the private sector, membership in boards or advisory committees employed by public authorities include individuals from all segments of society (e.g. representatives from academia, industry, and non-governmental organizations). Our search discovered that governments seek boards with external members to oversee and implement their AI strategies. This can take the form of providing advice on delimited matters or assigning a multiplicity of tasks central to the implementation or enforcement of these soft law programs.

On one end of the spectrum, boards have a circumscript role within the enforcement of AI strategies. They concentrate on tasks related to the “analysis and assessment of the ethical aspects of the use and implementation of AI”, are charged with thinking about how to implement AI principles, “review [the] impact of technology on fundamental rights,” or are asked to keep an eye on national and international AI trends [75], [92], [115]–[117].

On the other end, some countries assign these bodies with substantial responsibilities over the implementation or enforcement of their AI strategies. Finland’s board has the remit of developing a diagnostic for improving the private sector’s role in the AI ecosystem and drawing up an action plan for achieving it [118]. The Estonian government tasked its expert group with a similar directive as its Finnish counterpart, with the added responsibility of preparing draft laws related to AI and monitor the implementation of its strategy [119].

One of the most powerful boards is the one designated in Russia’s AI strategy. Its responsibilities encompass the supervision and coordination of all efforts related to the implementation of its soft law AI program. This includes formulating the action plan, creating performance indicators, monitoring activities, and serving as the node between government and external stakeholders in all matters related to the government’s AI efforts [120].

2.6.4.1.3 Research organizations and non-profits

A common theme for bodies with external members in research organizations and non-profits is a principal-agent relationship. In other words, these boards are constituted to ensure the accountability of the managing team in maintaining the entity’s sustainability and reaching the AI-related goals of their soft law programs [41], [52], [61], [94], [121], [122]. In one case, an organization tasked its ethics committee with not only overseeing its ethical use of AI, but also with the creation of its soft law program [123].

2.6.4.1.4 Professional associations

The membership of professional associations is composed of individuals who practice in a designated field. The soft law programs within these organizations appear to be educational in scope. They recruit members, who are generally not employed by the association, and ask them to periodically inform other members on any AI-related developments in the field or assist in the creation of ad-hoc training programs related to this technology [124], [125].